1. Introduction

Since the beginning of the twentieth century, the Mixteca region has received a

significant amount of attention from researchers. In spite of the existence of

what are now considered classic studies, along with recent ones analysing

diverse spheres of life in this region (Dahlgren, 1990; Pastor, 1987; Romero,

1990; Smith, 1973; Spores, 1967, 2007; Terraciano, 2001), when we compare the

volume of literature to the existing amount referencing the centre of Mexico

(the Nahua influence area), we find that interest in Mixteca has been lower1. There are micro-regions whose history is still waiting to be reconstructed,

and we have a good extent of documents to analyse that will open the door to

the exploration of new matters through the revision of particular cases of

study.

This paper examines some of the changes and continuities produced in ecological,

political and social spheres in a particular area of the ancient señorío (lordship) of Tlaxiaco, in the cañada of Yosotiche2, from the agricultural innovations that took place after the arrival of the

Spaniards and their interest in the exploitation of the indigenous workforce

and local fertile lands. Our analysis is based on two perspectives of study

that we consider complementary: on the one hand, on the political-territorial

conceptualization of Mixtec indigenous lordship and its adaptation to the

Spanish administrative model during the sixteenth century3; and on the other hand, on the approaches developed by the relatively young

discipline baptised as environmental history. The latter alludes to the

interaction of the human being with modified ecosystems, resulting in a double

transformation: the natural environment, along with administrative, political,

labour, social and even ritual relations between the peoples that interact with

said milieu (Worster, 1989).

Thus, the literature that supports the research is framed within those studies

that investigate the political characterization of the colonial Indian

community in New Spain as a corporate entity modelled by the need to adapt to a

new European administrative rationality (Ouweneel & Miller, 1990; Lockhart, 1992). After decades of research, it is well proved

that the Spanish administration rested on indigenous structures. Particularly

for the region that concerns us, ethno-historical and linguistic studies have

produced particular analytical categories essential for the examination of the

Mixtec political and territorial organization, both in pre-Hispanic times and

during the colonial period. Even so, the general model for the organization of

the territory still presents some significant gaps and generates debates

between academics. So, each new case study contributes to clarifying and

completing the proposed pattern.

To the date, the former señorío of Tlaxiaco had not been approached in all its extent and complexity4, and in particular, we can make some contributions in this respect through the

analysis exposed here. In order to do this, it is essential to take into

account the inquiries carried out by Kevin Terraciano (2001) and Ronald Spores

(2007) in the description of possible models of yuhuitayu-señorío, and by Margarita Menegus (2005, 2009) and John K. Chance (2004, 2010) around

the institution of indigenous cacicazgo (lordly estate) from the sixteenth century and its relationship with the cabildo (Spanish town council) or republic of Indians5.

On the other hand, the research is related to the first of the three trends

recognized by Stefania Gallini (2005: 5-6) within environmental history, which

addresses the interactions of certain human societies with their ecosystems and

the continuous changes produced thereon6. In America, inevitably many of these changes were triggered by the arrival of

the Europeans and their conquests, so the biological and cultural consequences

of transoceanic exchange have attracted interest for decades (e.g. Crosby, 1972; Sempat, 2006). In this context and keeping within the interests

of the present work, a pioneer researcher was William Cronon (1983), who

through the study of New England ecology, demonstrated the impact on the land

of the widely disparate conceptions of ownership held by Native Americans and

English colonists.

Mexico has been a fruitful place in research on the ecological aspects of

pre-Hispanic and colonial production and its relation to the socio-political

structural framework7. For the dynamics that concern us, the works of María de los Ángeles Romero (1990) on the production variations and the new economy raised by

the Spaniards in the Mixteca Alta, and Elinor G. K. Melville (1994) on the

impact of the introduction of wool cattle in the Mezquital valley serve as

examples.

The ecological change that we are interested to highlight particularly is the

one provoked by the introduction of sugar cane. The literature on this crop in

America is very prolific. Although numerous studies have privileged –due to their enormous importance in the geopolitical configuration of the Modern

Ages– an economic perspective of study, around the commercialization and slave trade

(e.g. Schwartz, 2004), there have also been attempts to take care of the social

aspects of its historical production, as we have observed in some of the works

carried out on cane production in New Spain (Sandoval, 1951; Motta & Velasco, 2003; Wobeser, 2004).

Paying attention to our specific area of study, the cañada of Yosotiche was referred to by Rodolfo Pastor (1987) in relation to the

production of sugar by wealthy Spaniards since eighteenth century. The dynamics

of conflict between communities and landowners since the disentailment process

taken place at the mid-nineteenth century have also attracted the consideration

of some researchers (Sánchez Silva, 1998: chapter VI; Hamnett, 2002; in more detail than the previous

ones, Chassen, 2003). The latter took the path opened by John Monaghan (1990,

1994), the first researcher to observe the cañada in detail. Attracted by contemporary anthropological problems, and in relation

to the dynamics of land ownership during the nineteenth century, he also made

incursions into some aspects of the colonial past, especially in the

composition and functions of lordly estates. His contributions constitute, in

good measure, the basis of the research presented here.

In particular, the contribution we make extends Monaghan’s field of analysis by incorporating an integral vision of the Tlaxiaco lordship

in order to be able to compare the cañada to other regions of the province, to pay attention to the models of yuhuitayu and cacicazgo, and to observe the corresponding land tenure regime, and, consequently, the

interrelation between different types of jurisdictional traditions: the

indigenous –studied from its own categories– and the European one8. In this way, the study of the biological modification of a particular

ecosystem allows us to make inferences about the changes and continuities of

socio-political relations, therefore contributing to our understanding of a

general model of Mixtec political territoriality.

In order to carry out this work, besides the bibliographical review on the

different issues addressed, a wide corpus of archive data was consulted, along

with field work, oral history compilation, archaeological information review

and indigenous toponymy study9. In the first section, we will characterize our area of study based on its

environmental dynamics, the behaviour of political-territorial structures and

the institution of the cacicazgo; we will then observe the sequence of lawsuits provoked by the desire to

control the land in the cañada, which is intensely linked with the introduction of foreign crops –especially sugar cane– and with the alteration of an ancestral ecological complementarity, explained

in the following section; and finally, we analyse the changes and continuities

produced in Yosotiche in terms of jurisdiction and land exploitation.

2. Socio-Environmental Characteristics of the Mixteca Region

2.1. General environmental characteristics

The Mixteca is one of the largest regions amongst the eight that currently make

up the Mexican state of Oaxaca. It occupies the northwest section of the state,

but considered as a cultural region (defined principally by the presence of tu’un savi or Mixtec language speakers and some shared cultural practices) it also extends

to the west part of the Oaxaca coast, the south of the state of Puebla and the

eastern strip of Guerrero. The terrain presents formations with different

heights but very intricately connected, which leads to a small number of large

or open plains and valleys. However, this circumstance has not impeded the

development of agriculture on practically all types of surfaces. The topography

(plains, hills, mountains, crags, valleys) and climate (hot, temperate, cold,

and dry, demi-dry, humid) are very diverse. As a result, there is a high

assortment of micro-ecosystems, which noticeably affected the historical and

cultural development of the region (Spores, 2007: 5-8).

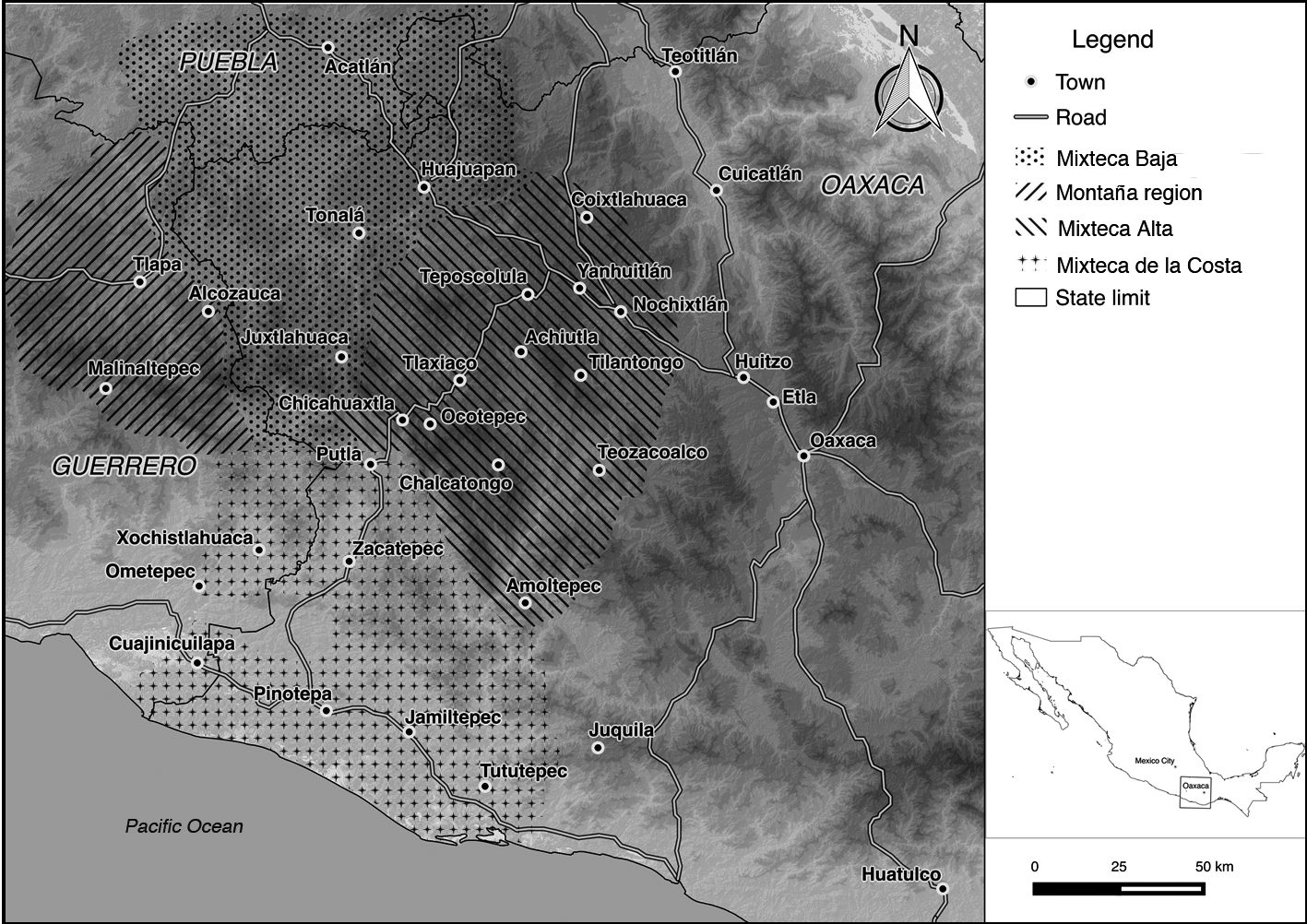

Figure 1

Map of the Mixtec sub-regions and their main towns

Source: preparation by the author.

Conventionally, this vast area has been divided into three geographic regions

depending on natural environment and topography: the Mixteca Baja, with arid

and semi-arid climate; the Mixteca Alta, with temperate and cold climates and

both semi-dry and humid zones; and Mixteca de la Costa, with predominance of

hot and humid climate (Figure 1) (Spores, 2007: 7)10. Since pre-Hispanic times, political alliances were established among these

three sub-regions, and these promoted the composition of exchange networks of

products from different ecological niches. This dynamic allowed the economic

self-sufficiency of Mixtec large political units, distributed generally over

big vertical spaces, which encompassed a variety of types of soils and

climates. But this latter feature did not mean to say that the territorial

extensions were continuous (Pastor, 1987: 43-44). This dynamic is observable

through the jurisdictional relations established by both the yuhuityu and the cacicazgo, which we characterize below to achieve an adequate understanding of the

phenomena analysed in the surroundings of the cañada.

2.2. Yuhuitayu, cacicazgo and land tenure

The larger autonomous political units, formed as a political arrangement created

through dynastic alliances, were denominated yuhuitayu, and in the sixteenth century this reality was translated and conceptualized as

kingdom or señorío (lordship). In turn, it was divided into other smaller entities: the ñuu, which we can understand as a city-state, and the siqui, dzini or siña, the neighbourhoods (Terraciano, 2001: 165, 248)11.

The political-territorial categories were closely linked with the social ones,

since both were ultimately under the powerful influence of kinship12. Ronald Spores (1967: 9-10; 2007: 87, 99, 106) proposes that the yuhuitayu, later transformed into cacicazgos under Spanish domination, had a hierarchical organization, headed by a supreme

authority called yya tnuhu or yya toniñe, “king” or “lord”, and by a group of “nobles” or “principals”, tay toho. These two social classes controlled the positions of power and authority, the

productive lands, the natural resources, the mode of production and

distribution of goods and services, and the ceremonial institutions, besides

receiving tribute (daha), and personal services from the inhabitants of the yuhuitayu, the tay ñuu or tay yucu, the “common people”, and the tay situndayu, called terrazgueros in Spanish (tenant farmers). In return, its population received protection,

ceremonial patronage and titles of usufruct for the cultivated lands.

From sources in the sixteenth century Mixtec language, it was deduced that the

indigenous universe divided the land into three categories (irrigated,

naturally fertile and sterile), which in turn were classified in other

subclasses. The intensive labour of the farmers was organized in two levels,

systematized in Table 1:

Table 1

Levels of organization and kinds of cultivated lands

| Level of organization | Kind of cultivated land | Description |

| House | ñuhu huahi or solar | Plots associated with a particular domestic unit, |

| (property of the ancestral | both of lords and commoners |

| house) | |

| ñuhu chiyo | Ancient inalienable patrimonial lands |

| | of the house |

| Neighbourhood | ñuhu ñuu | Lands claimed by the ñuu |

| ñuhu siña | Lands of the neighbourhood |

| ñuhu aniñe | Lands of the lordly house or the palace (part |

| ñuhu nidzico | of the colonial cacicazgo) |

| | Noble’s lands, acquired by purchase |

Sources: made from the information collected by Pastor (1987: 38) and Terraciano

(2001: chap. 7).

The institution of the cacicazgo was established in colonial times when recognizing the rights of the principals

and of the pre-Hispanic señores naturales (native lords) of the different spaces of New Spain and other places of the

Empire. A very general idea leads us to consider the caciques and cacicas (male and female lords) as mediating figures between the Spanish administration

and the indigenous society in the Indian towns, where they maintained their

ancestral rights and privileges: goods and services rendered by the commoners

attached to them (terrazgo), market rights, tributes, properties bonded to the lineage and succession, and

estate rights, among others. In this way, the cacicazgo –understood as an exercise of a special jurisdiction– consolidated a group of power that occupied an important place in the colonial

political apparatus for long time in the Mixteca region, which had continuity

as an important landowner until the first moments of an independent Mexico

(Chance, 2010).

The main mechanism of integration and maintenance of cacicazgo in the Mixteca was the creation of alliances between the heads or the direct

heirs of the different royal lineages, sealed via matrimony. Also, as Ronald

Spores (1974: 297) pointed out, this strategy was significant in the creation of a social, political, and economic network that linked

numerous communities and political domains into a broad social field bridging

varied geographical zones ranging from tropical lowlands to highland valleys.

Unlike what happened in central Mexico, in the Mixteca, the power of stately

houses remained strong during the sixteenth century (Terraciano, 2001: chap.

7). On the political level, the nobles and principals, the tay toho, came to occupy the key positions of the town council, whereas the old supreme

authority, yya tnuhu or yya toniñe, was recognized like natural lord and erected to the category of cacique (Spores, 2007: chap. 8).

Table 2

Colonial land typology

| Land type | Description |

| Fundo legal or extension of the populated area | Lands where the urban nucleus is settled. |

| Lands of the community | Propios: served to defray the maintenance of the community (payment of salaries, tribute, and judicial and worship costs, among other harges), through the profits derived from their exploitation or lease. Comunales (communals): they were distributed in plots for their tillage and thus obtain the maintenance of the family. Community forests and grazing lands: for private use by all members of the community. Lands assigned to citizens and servants without access to communal lands. |

| Lands of the neighbourhood | Lands divided and worked separately by individuals and families in the neighbourhoods. |

| Private lands | Generally, in the hands of the nobility. |

Sources: drawn from the researches developed by Taylor (1998: chap. 3) in the

Valley of Oaxaca and by Menegus (2009, 2016) in the Mixteca.

A very relevant social group linked to the cacicazgo was the tay situndayu or terrazgueros, who paid an income to occupy lands, worked plots and made personal services.

In other words, their condition combined the economic rent and the lordly bonds of personal dependence. In this way, the cacique possessed

the direct ownership over the lands, and the terrazguero the beneficial ownership (Taylor, 1998: 59; Sempat, 2006: 286; Menegus, 2009: 56).

This scene of indigenous relationships and land tenure was forced to adjust, at

least nominally, to a scheme of European tradition that sought to become

homogeneous throughout the viceroyalty. In Table 2, we systematize the new land

typology instituted.

In the Mixteca Baja the terrazgueros were especially numerous, and although the Crown tried to introduce them into

the pattern of regular tributaries through the creation of Indian town councils

(later called repúblicas de indios, “Indian republics”) and by giving of land grants during the sixteenth and early seventeenth

centuries, there is evidence of the creation those type of councils inside the

territory of the caciques: seemingly, the republic was given only urban core for their settlement and propios lands, omitting comunales, those of communal use. So, for their subsistence they continued relying on the

cacique’s lands and on the payment of a terrazgo, personal service and obedience to him (Menegus, 2009: 50, 56; 2015)14.

In other words, when the yya toniñe became caciques, they came to possess the ñuhu aniñe and their ñuhu chiyo with a “patrimonial” sense attached to the European juridical tradition, which included the terrazgueros associated with their lordship (Menegus, 2005). In this sense, Terraciano

(2001: 206) suggests that noble houses subsumed many corporate landholding responsabilities in the Mixteca […]. This tendency seems most pronounced in the Mixteca Baja, where yya normally

considered the lands and laborers of dzini [barrio] as part of their patrimonies15. As we shall show later, we believe that these relations of stately dependence

also operated in the ancient lordship of Tlaxiaco, although with a significant

particularity: disengaged from the main ruling lineage.

All these features lead us to emphasize the importance of the cacicazgo as an administrator of the local economies through the possession of lands and

the management of the labour force of its terrazgueros. This allowed the cacicazgo to build notable family estates and to be a key aspect of the economic

structure of colonial Oaxaca. One hypothesis consists in that this situation

could had been maintained for a longer time in the Mixteca than in other areas

in New Spain due to the mediating need of the caciques in a region where the presence of Spaniards was not as intense as elsewhere

(Spores, 2007: 82).

2.3. Territoriality and landscape in the yuhuitayu of Tlaxiaco

The Mixtec toponym of Tlaxiaco was and also today is Ndisi Nuu, “Good Sight”. In this vast yuhuitayu coexisted Mixtec population (the most abundant), Triqui (in minority, in the

west and southwest parts), and Nahua (since the establishment of a Mexica

garrison in the mid-fifteenth century, promoted by the Emperor Motecuhzoma

Ilhuicamina [1440-1468]). With the arrival of the Spaniards, this space was

reconfigured under the thrust of the Laws of the Indies in a complex system

consisting of a cabecera (head town) and several sujetos (subject villages).

The more detailed description of the jurisdiction that we have so far is dated

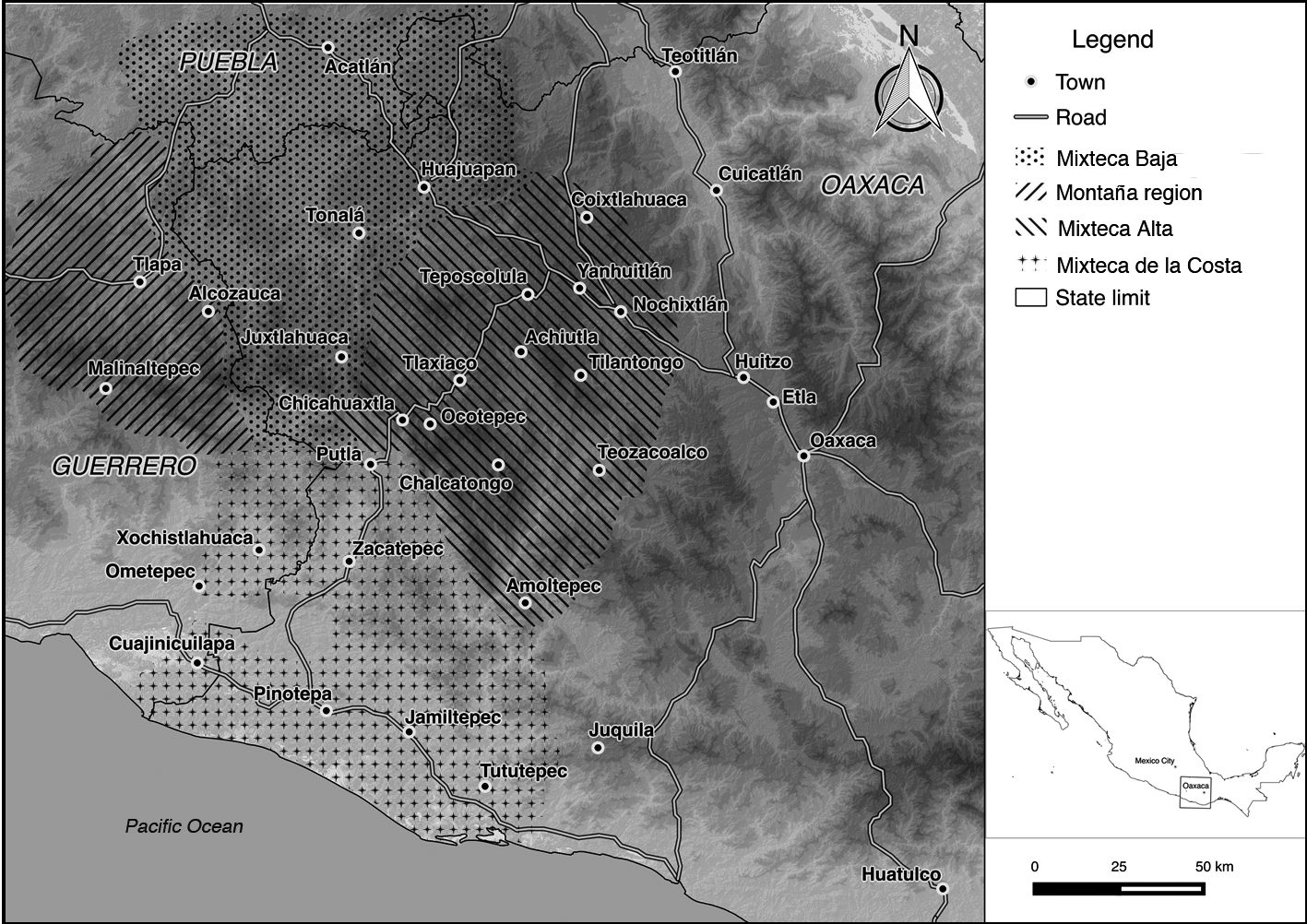

from 1599, and consists of the proceedings made by Ruy Díaz Cerón regarding the plan to accomplish one congregation or reducción of villages16. We identified the historical places mentioned in the document with current

localities correlating the historical information supplied within, especially

the distances between settlements, with data obtained using fieldwork, the

analysis of toponymy, and the available archaeological record. The result is a

jurisdiction consisting of the cabecera of Tlaxiaco and thirty-one estancias (subject villages), spread out from north to south 80 km, and from east to west

along a 35 km wide strip (Figure 2)17. This space was not a continuum; instead, the territories were interspersed. In

the southeast, the villages under Tlaxiaco were mixed and bordered with those

of the señoríos of Chalcatongo and Yolotepec-Ixcatlán, and in the west-southwest with Cuquila, Chicahuaxtla, Putla and Ocotepec.

The traditional historiography concerning the Mixteca has presented Tlaxiaco as

one of the most important lordships in the area at the time of the Spanish

arrival (Dahlgren, 1990). But the archaeological and ethnohistorical studies,

the latter supported mainly on the analysis of codices or pre-Hispanic

pictorial manuscripts, reveal that there was a progressive concentration of

power around the small valley of Tlaxiaco, which culminated in the decade of

1550. We summarize below our interpretation and its implications.

Figure 2

Map of the villages under the jurisdiction of Tlaxiaco, 1599

Source: preparation by the author based on the “Diligencias para la congregación de Tlaxiaco”, 1599. Archivo Histórico Municipal de la Heroica Ciudad de Tlaxiaco.

During the Classic period (400-1100 A.D.) the valley had a dispersed settlement

pattern, with the dwellings at the top and on the slopes of the hills

encircling it. Also, in the area of influence of the subsequent señorío, existed other centres that concentrated significant quantities of population

and could be conceived as effective market places18. During the Post-classic period (1100-1521 A.D.), a process of progressive

densification of the population in the valley began (Spores, 2005: 14-15), and

in the sixteenth century, the pre-Hispanic yuhuitayu begun to articulate in political and administrative structures according to

Spanish custom due to the establishment of one church and later of a Dominican

monastery in 1548, and with the gathering of the population around it,

initiated in 155319.

Some sources from the middle of the sixteenth century show a hierarchical

complexity not appreciated in other Mixtec lordships: Tlaxiaco came to be the

head of nine subject towns, which in turn had other subordinate villages, 108

in total20. The deciphering of the preserved codices, especially the reverse side of Codex Bodley, also supports the idea that Tlaxiaco gradually acquired political power from

the Classic period onwards. In this process, the establishment of marital bonds

that served to seal strategic alliances between the ruling dynasties became

essential, also as a means of obtaining the legitimacy that emanated from the

most renowned lineage with divine origin from Tilantongo (Jansen, 2004).

We are inclined to think that the ancient yuhuitayu of Tlaxiaco, before the Spaniards arrival, could be a compound or complex señorío, that is, with various yya toniñe or “kings” in charge of certain sections, but sharing authority in some way21. After the conquest, this situation would have been simplified and the power

would concentrate around the cabecera of Tlaxiaco through an assorted combination of mechanisms, such as the

congregation of the population around the monastery.

To finish contextualizing our space, we need to characterize its environment.

The judge that crossed the jurisdiction in 1599 wrote down the characteristics

of the climates (called temples in Spanish) assigned to each village (hot, temperate, cold), their crops and

means of maintenance (called granjerías), and the use intended to be allocated to barren lands by the Spaniards once

four congregations of villages were set up22. Summarizing, the majority of the settlements were in places described as cold,

in elevations over 2,000 metres above sea level. Seven places were temperate,

placed between 1,600 and 1,900 metres above sea level; two of them were in the

north edge of the jurisdiction, in the transitional zone to the Mixteca Baja,

where the land turns more arid; one is situated on the slopes of the mountains

that flank the cañada of Yosotiche, and the rest are in the southeast area of Tlaxiaco, in the

mountain range that runs to the coast. Finally, two villages are said to be

hot, and they lay at the bottom of the cañada, at 800 metres above sea level.

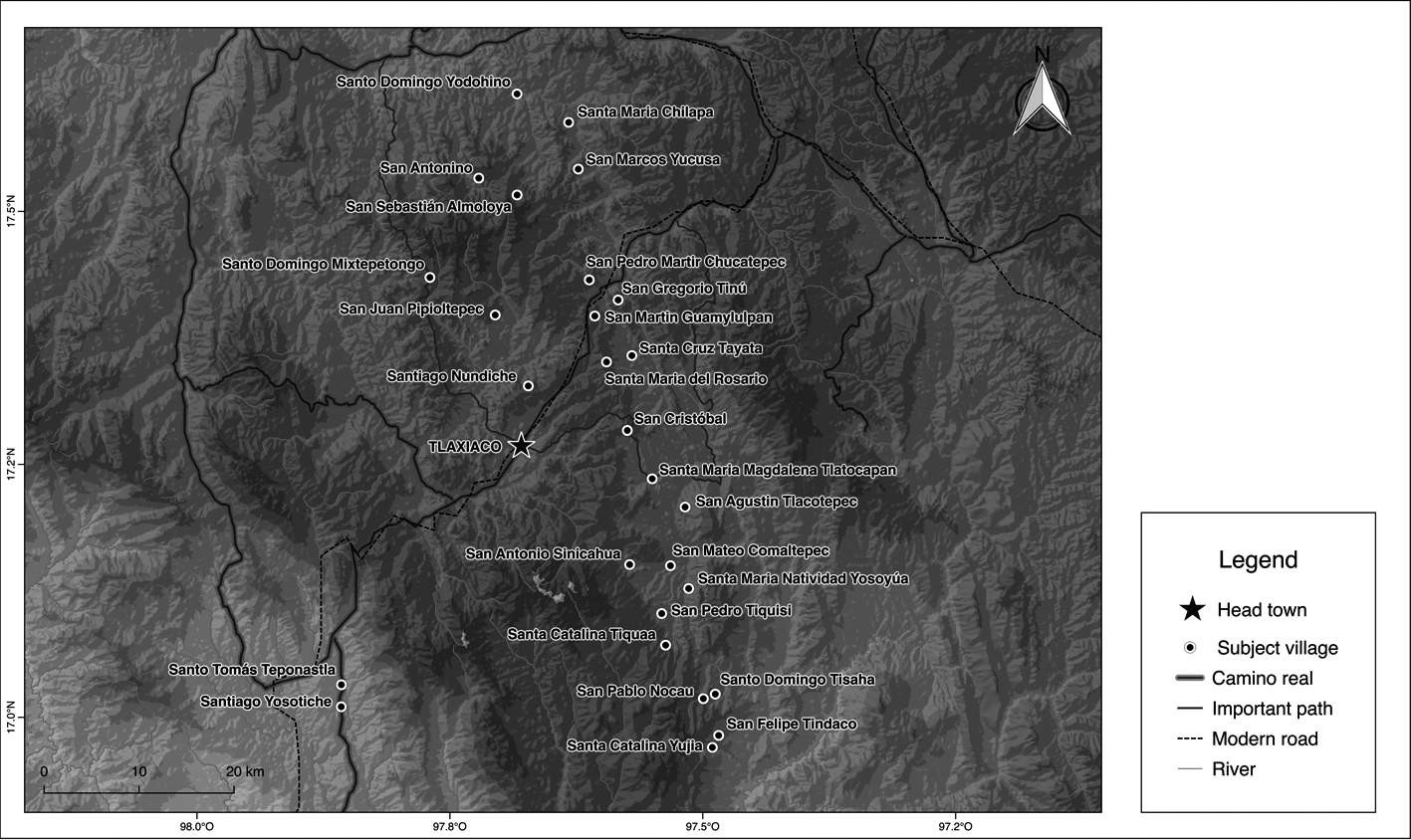

Figure 3

Map of the cañada of Yosotiche ecosystem today and its main villages

Source: preparation by the author.

Without analysing the productive capacity of each village, which was between 3

and 13 almudes of corn sowed by each tributary Indian23, we can generally observe that corn and beans were present all over the

territory, just like particular fruit trees, that wheat and maguey were grown

in some cold areas, that banana and citrus fruits were typical of temperate

places, and that cotton and cocoa were grown just in hot lands. The Spanish

authorities believed that a good part of the empty lands between the villages,

excepting the mountainous and intricate places, could be good for the

establishment of estates for small livestock or mares, or growing corn and

wheat fields.

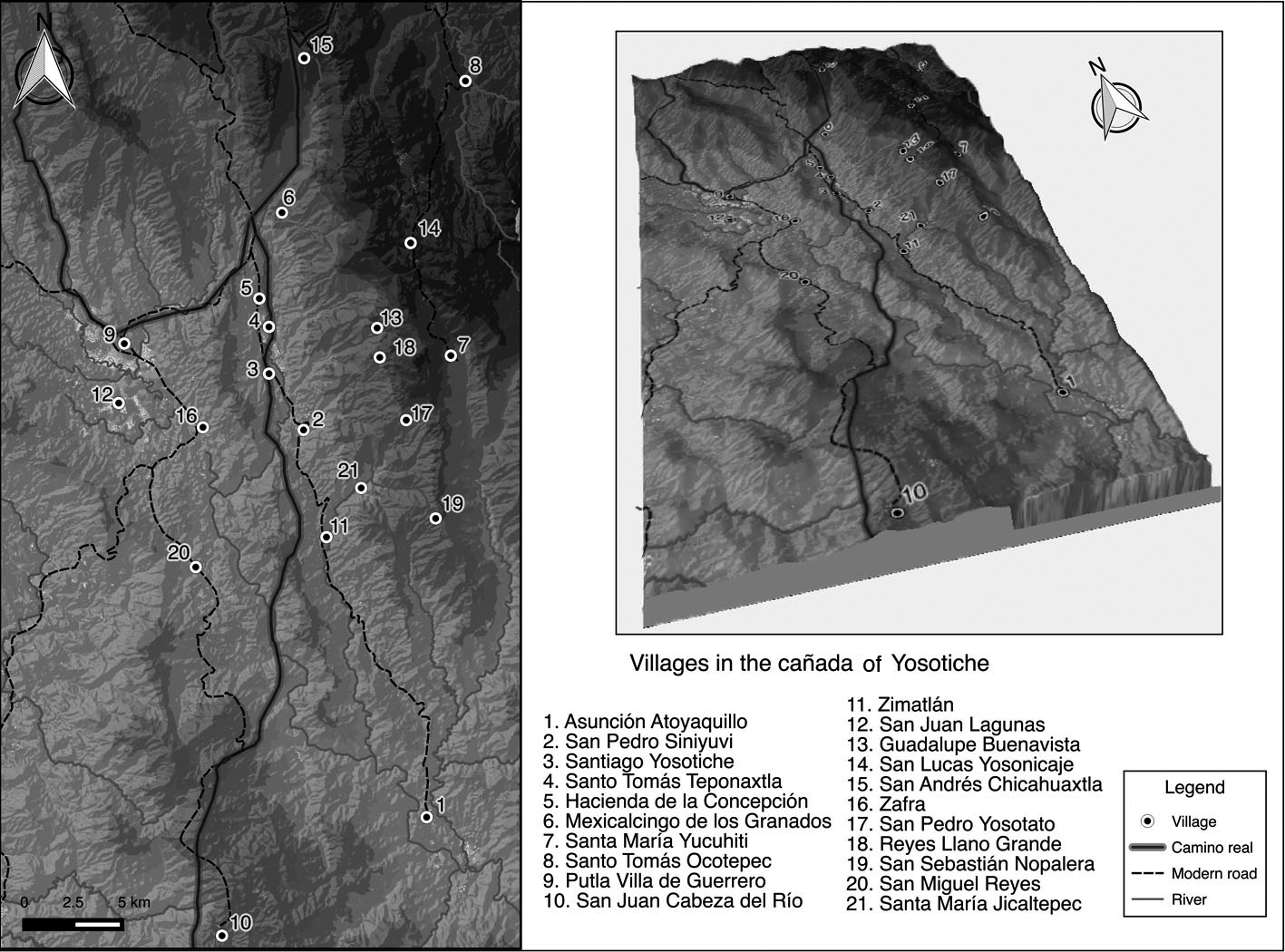

In this special context, the cañada of Yosotiche, situated at about 70 km south of Tlaxiaco, occupies a prominent

place. It is 12 km long and 3 km at its widest, at the bottom of a valley that

is shaped by alluvium plains. But, what we recognise as the ecosystem of the cañada encompasses in addition the settlements upon the heights and slopes of the

mountains that limit it. This territory is in a transitional zone between the

cold lands of the Mixteca Alta and the hot lands of the Mixteca de la Costa,

and is irrigated by a series of rivers that originate in the high sections of

the mountains and flow to the south (Monaghan, 1994: 144) (Figure 3). These

characteristics make the cañada a perfect stage to sow, both on the slopes and upon the valley floor, a wide

range of products, especially those imported from the Old World, like banana

and sugar cane. The “royal route” (camino real) passed through this space, connecting the central Mixteca Alta to the important

coastal town of Pinotepa del Rey, and from there, to Huatulco, the most

important Pacific port during the two first thirds of sixteenth century, until

it was displaced by Acapulco (Romero, 1990: 28).

With these features, it is not strange that Tlaxiaco aspired to control lands in

the cañada since pre-Hispanic times, even when it was quite far from the cabecera and was, and is still today, difficult to reach by paved roads.

3. Productive context and dynamic of land tenure in the cañada of Yosotiche

3.1. Crops in the sixteenth century: coexistence of native plants with those of

new introduction

We do not know with certainty which products were grown predominantly in

Yosotiche and adjacent areas before the Spaniards arrival, but the sixteenth

century documents state that around 1550, traditional Mesoamerican crops

coexisted with new plants introduced by Europeans: abundant cocoa gardens and

plantations of corn, chilli and cotton, as well as bananas, wheat, mulberry, fruits and seeds from Castile and sugar cane were raised by means of irrigation systems. In addition, in the

rivers that cross the bottom of the valley, trout were fished, and all these

products supplied the markets of the Mixteca Alta and Baja24. That is to say, the cañada was conceived as an appreciated greenhouse of tropical products for a large part

of the northern territories.

The strong presence of cocoa refers to two outstanding matters25. On one hand, cocoa was grown in gardens, just like bananas, which imply the

presence of irrigation systems26. These could also benefit other crops, like corn, whose productive cycle would

be different from that raised in other heights and conditions. And on the

other, cocoa was a high-value product in the pre-Hispanic economy, because,

among other features, it was used in ritual contexts and served as coin for the

payment of the tribute, even in early colonial times (Aranda, 2005)27. At the beginning of the seventeenth century, Mixtec Indians still trade with

cacao and had reales invested in this product, despite the efforts of the viceroy Luis de Velasco “The Old” to eradicate this practice (Romero, 1990: 107-108). The fact that the plots

where the gardens were grown had Mixtec names, and were assigned to certain

individuals to benefit from them, allows us to think that these lands would be

under a particular land tenure regime. We will discuss this matter later.

The particular conditions of the ecosystem of the cañada allowed the colonial political and administrative complexes we call cabecera-sujeto to develop an ecological complementarity system. John Monaghan (1990:

349-351; 1994: 148) identified it as Na Sama during his anthropological and ethno-historical research developed in the

1980s, and it consisted of the following. The scarcity in the mountainous

localities of the cañada (among others, Santa María Yucuhiti, Santiago Nuyoo and San Pedro Yosotato) began in July and gave way to

the months denominated yoo tama (of famine); at this time the corn cultivated at the bottom of the valley could

be available, because it was sowed between December and January with irrigation

systems and harvested between July and August. Then, when yoo tama began in the valley, between March and April, they could get the mountain maize

seeded between February and May and harvested between November and January28.

Sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum) arrived in the American continent from the Canary Islands, from where

Christopher Columbus transported it to the island of Hispaniola on its second

voyage in 1594. From there, it passed to Cuba and Puerto Rico. Its introduction

to New Spain was carried out by Hernán Cortés, who had become familiar with it during his service in Cuba, and soon cane

experienced a quick entrenchment in the central lands of Veracruz and in the

region of Cuernavaca and Cuautla (in the present Morelos), part of the land

assigned to the Marquisate of the Valley of Oaxaca, the patrimony of the

conqueror, cultivated with a view to export. Throughout the sixteenth century

it spread south and west to the warm lands of Michoacán and Jalisco, to the rich valleys of Atlixco and Izúcar, near the city of Puebla, and to different points of the present state of

Oaxaca (Sandoval, 1951: chaps. 2, 3; Wobeser, 2004: chap. 1).

The institution of the encomienda, which nominally respected the right to indigenous property, intervened

decisively in the founding of the first sugar mills29. However, the Spaniards soon deployed legal and extralegal mechanisms to gain

access to the lands and waters of the Indians to plant and process sugarcane:

land grants, special licenses, purchase, lease, donation (in the case of

religious congregations), and also dispossession (Sandoval, 1951: 35, Wobeser,

2004: 44 et seq.). Production was quickly subject to tax regulation. Under a law issued by the

Catholic Monarchs in Granada in 1501, agricultural products of the Indies were

encumbered with a ten percent (diezmo, in Spanish), which included sugar (Sandoval, 1951: 37).

In New Spain, after an initial period of limited expansion, between 1600 and

1690 there was a very remarkable growth and stabilization of production due to

the abolition of some restrictive measures, the introduction of black slaves,

the availability of credit, the large supply of water and land derived from the

dramatic demographic decline, as well as to the increase in sugar demand. Then,

between 1690 and 1760, it supervened a general period of crisis due, among

other factors, to the imbalance of supply and demand, which led to a withdrawal

to the domestic market. Finally, in the last third of the eighteenth century

production was again recovered (Wobeser, 2004: chaps. 2, 3)30.

The workforce employed underwent various regulations over time. In the

beginning, indigenous labour was mobilized by virtue of the services associated

with the encomienda, and also Indian slaves who had acquired this status by war and blacks

purchased by royal licenses were incorporated. New Laws issued in 1542 decreed

the liberation of the indigenous population, and this measure was reinforced by

successive decrees that prohibited the payment of the tribute to the Crown or

the encomendero in personal service. The door to the lease of the indigenous labour force had

been set up. In the time of the Viceroy Martín Enríquez (1568-1580) the distribution of forced labour (repartimiento de indios) was instituted. It meant that the landowners went to special judges (jueces repartidores) to assign them Indians who worked in a rotating way in return for a daily wage.

Viceroy Conde de Monterrey (1595-1603) prohibited this type of forced labour

and urged the use of free and paid indigenous workforce. A royal decree issued

by Philip III in 1601 went further and banned all indigenous enslaved or

wage-earner in the sugar industry. This set the stage for the massive

acquisition of black labour, but despite these measures, many documents inform

us that indigenous people continued to be employed in the sugar industry

(Sandoval, 1951: 51-64).

The coexistence of workers of both types is also related to the differentiation

of activities in production. The farming of sugar cane was very demanding,

because, as well as the attention required to control the irrigation of the

fields, the plant needed special care, which demanded a numerous workforce,

especially in the time of cutting, preparation and hauling the reeds to be

placed inside the sugar mill boilers31.

Systematic exploitation of cane in the cañada of Yosotiche began at the end of the sixteenth century by Spaniards who

obtained land thanks to the land grants or through their leasing. The first

owner we have news about was the encomendero of Tlaxiaco, Matías Vázquez Laínez, who was given in 1585 a grant to establish a sugar mill, houses for service

people and corrals, as well as the mountains, pastures and waters necessary for

the sustenance of his property, plus a cattle ranch32. Thereafter, there were numerous grants to establish mills, on lands leased to

the community of Tlaxiaco or to cacicazgos that extended their jurisdiction over part of the cañada, as Ocotepec, Chicahuaxtla and Zacatepec. It is to be noted that all the

production units were modest, and that no great factory was set up until the

nineteenth century33. It is complicated to establish a certain sequence of progression of the mills

in the area due to the fragmentary documentation available. However, we observe

that it was at the beginning of the eighteenth century when the cultivation

turned actually systematic. From 1715 onwards, grants increased, probably

thanks to the decrease in the need to exploit community sowings, when the royal

and community tribute began to be demanded exclusively in money, no longer in

kind, and due to the greater availability of indigenous workforce because of

their population recovery (Taylor, 1998: 96; Sempat, 2006). Some of the best

known mills were La Concepción (later, Hacienda de La Concepción), San José, San Vicente and Nuestra Señora del Rosario34.

Sugar cane cultivation meant a severe blow to the system of ecological

complementarity that people had developed for ages. Because of crop

substitution, corn that saved the yoo tama months of the mountain villages began to be scarce, and the inhabitants who

frequently covered a short three hour distance to the valley floor in order to

exchange products, were forced to sell their labour in the sugar mills and

plantations (Monaghan, 1990: 350). These different forms of land use centred

around sugar cane, modified the labour relations of the inhabitants of a

substantial area of the jurisdiction. Nonetheless, a detailed analysis of the

system of land tenure and the operation of the cacicazgo allows us to observe an interesting local perspective regarding the survival of

inherited relationships of the ancient yuhuitayu. Below we will summarize the process of jurisdictional adaptation in the cañada to better understand this situation.

3.2. Jurisdictional problems in the cañada: old and new lawsuits

In this section we will briefly observe some of the problems involved in the

adaptation of the framework of pre-Hispanic indigenous territoriality to the

European one, through the lawsuits brought between two types of agents with

their peers: on the one hand, the Spanish encomenderos, and on the other, the indigenous entities of the community and the cacicazgo.

In terms of territoriality and according to Rodolfo Pastor (1987: 68-69), the

distribution of encomiendas in Oaxaca was based on the organization of the tribute collection centres of

the Mexica Triple Alliance, which in turn reproduced the divisions of the

lordships. In some cases, as in ours, the encomienda preserved the integration of different ecological niches. Thus, in general, we

observe that this institution was based on the principle of personal

association (Personenverband) practiced in pre-Hispanic times, as opposed to the territorial association (Territorialverband) typical of the European tradition of the Modern Age (Hoekstra, 1990). However,

the misunderstanding of the pre-Hispanic territorial organization sometimes led

to legally match some small subject lordships to the larger ones, and the first

were granted separately. Therefore, the encomienda mediated in some extent in the subsequent demarcation of territory, tearing

apart some great lordships (Pastor, 1987: 69). It is likely that the ambitions

of the encomenderos around the territories of the cañada of Yosotiche came to foster the latter in Tlaxiaco.

The vast province of Tlaxiaco was first granted to Juan Núñez Sedeño, but in 1528 it was reassigned by Hernán Cortés to the conqueror Martín Vázquez Laínez, who owned, in addition, the neighboring towns of Mixtepec, Chicahuaxtla,

Ocotepec and Atoyaque, with their respective subject villages35. Between 1531 and 1533 Martín Vázquez held a lawsuit with Francisco Maldonado, encomendero of Achiutla and Tecomaxtlahuaca, both in the Mixteca, on the rights of the

village of Atoyaque (today Asunción Atoyaquillo, located at the southern end of the cañada)36. A few years later, between 1538 and 1541, it was Francisco Maldonado who

started a legal action against Martín Vázquez for the partition of the encomienda of Tlaxiaco, where the towns located in the cañada were especially involved37. Finally, in 1544 Francisco Maldonado requested that the Indians were reunited

as before, for the benefit of both the natives and the encomenderos. In this agreement Martín Vázquez regained all Tlaxiaco jurisdiction, including the cañada subject villages of Teponaxtla and Ypalestlahuaca (corruption of the Nahua name

of Santiago Yosotiche), but lost Ocotepec and Atoyaque38. It seems that from then onwards, despite lawsuits filed by the indigenous

entities to define their limits, the successive encomenderos did not revive the matter again39.

Let us observe what happened in the indigenous context. The town of Santa María Yucuhiti, then a subject locality to Ocotepec, litigated against Tlaxiaco by

the domination of the cañada. The matter was resolved in 1588 and countersigned in 1591: the Audience gave

Ocotepec the lands located on the slopes of the mountains, and Tlaxiaco the

fertile plains of the bottom of the valley. Both then rented part of the cañada to Spanish plantation owners and the slopes for the pasture of sheep and goats40.

In the eighteenth century the conflict flared up again. Tlaxiaco claimed to

Yucuhiti, who then had consummated its separation from Ocotepec and held the

title of town by itself, lands on the slopes and in the valley. But a royal writ issued in

1702 protected Yucuhiti in its possessions, and colonial authorities ordered

the establishment of boundary markers and the formal demarcation of these

villages. In 1732, the peoples of Tlaxiaco presented a new request and, as they

argued later, the sentence was favourable to them and were given new titles

(which then were misplaced) protecting the possession of Santiago Yosotiche and

Teponaxtla, in the valley bottom41. In 1750, Yucuhiti accused Tlaxiaco, arguing that many of its people had

emigrated and settled permanently in the cañada, penetrating the lands of Yucuhiti. Finally, the conflict reached a resolution

in 1763: Yucuhiti confirmed its possessions and Tlaxiaco requested the

legalization of its lands in the cañada and in the rest of the jurisdiction42. Due to subsequent population pressures, Yucuhiti ended up losing control of

the west slopes and retained the eastern ones (Monaghan, 1990: 356).

Some of the leases made in the cañada were transferred from one village to another within the framework of these

litigations. In 1733, after the town of Tlaxiaco won a lawsuit and recovered

certain lands, it began to receive the benefit of various leases that were made

with Ocotepec. Six years later, Tlaxiaco requested to terminate these contacts

that had continued irregularly, arguing the small amount of money they received

for land and the damage that the herds of goats possessed by one of the lessees

caused to the surrounding indigenous crops43.

Thinking about the dynamics of these lawsuits together begs the question: did

the conflict begin in the indigenous sphere, before the arrival of the

Spaniards, or the distribution of encomiendas and the differences between the encomenderos detonated the problems between Tlaxiaco and Ocotepec? The towns of Santiago

Yosotiche and Teponaxtla were recognized as subject villages of Tlaxiaco in

1538, at the moment of the distribution of the spheres of influence between the

two encomenderos, and so they appear also in 155044. Thus, we believe that they were part of the expanding and consolidating yuhuitayu of Tlaxiaco, just before the arrival of the conquerors. What seems clear is

that the high productive potential of the cañada was an attraction that both Spaniards and Indians wanted to take advantage of,

supported by the Spanish-American land tenure regulations and motivated by the

high profitable new productive activities that the New World began to hold.

4. Changes and continuities: land use and jurisdiction

What has been shown so far allows us to observe some remarkable changes and

continuities about different aspects of land use (productivity, work systems,

environmental impact) and the adaptation to the new Hispanic jurisdictional

system. In this section, we highlight some relevant points.

From an economic perspective, the introduction of new vegetable and animal

species became highly profitable to these indigenous communities, unlike what

happened in other areas of New Spain, where the benefit resulted in the

expansion of European rural property45. In the case of Tlaxiaco, we have observed how sugar cane was cultivated

fundamentally on community lands leased to Spaniards (civilians and also

ecclesiastics), so the profits obtained fed the community treasury which

covered expenses of the town46. Before the cane, sheep and goats had also become an important source of

income, benefiting the encomenderos but especially the Indians, both caciques and communities (Romero, 1990: 91)47. The nobility as well as the community of Tlaxiaco was especially enterprising

in regard to this activity, even going so far as buying some estates that had

been previously granted to Spaniards48.

In the cañada of Yosotiche, the aforementioned lawsuits sought to consolidate the territories

of the yuhuitayu of Tlaxiaco and Ocotepec in the most advantageous possible position for the

exploitation of new productive activities, through community use or leasing

them to Spaniards. Sugarcane affected significantly the ecological

complementarity that guaranteed the everyday sustenance of the peoples of that

ecosystem. However, in broader economic terms, its cultivation supposed a very

limited contribution compared to other regions of New Spain, and the

circulation of the product was local. In proportion, the production of Oaxaca

was significantly greater in Huajuapan and surrounding areas, in the Mixteca

Baja; in Putla, Jicayán and Pinotepa, on the Coast; in Cuicatlán and Teotilán, at the northeast; in the valley of Oaxaca, and in the area of

Nejapa-Tehuantepec (Spores, 2007: 324). Mid-eighteenth century marked a

significant watershed in the increase of production in Yosotiche, but still the

production did not enter the international market. The management of sugar

mills by wealthy Spaniards allowed the formation of important regional fortunes

arisen from what Rodolfo Pastor (1987: 292) called the sugar emporium of Tlaxiaco49.

Regarding the labour employed in the agricultural enterprises of the cañada, we would like to emphasize two aspects. At first, the encomenderos made use of the personal service of the Indians to obtain profits by means of

tribute and to roll out their personal companies. We suppose that those

companies also employed forced Indian labour50.

However, in the Mixteca there was no mass movement of Indians to plantations or

farms, and extremely coercive agricultural work was not part of the picture

(Spores, 2007: 327-28). Even though the parish registers leave some evidence of

blacks and mulattoes51, and we know that Tlaxiaco was one of the slave-buying points in the Mixteca

and that they were engaged in the sugar mills (Motta & Velasco, 2003, Spores, 2007: 204-5), no studies have yet been conducted to

systematically assess their situation in the jurisdiction52. Oral accounts compiled in Yosotiche omit the historical presence of blacks

and, on the contrary, they stress the use of Mixtecs and mestizos in the mills

and estates. Eighteenth-century sources tell us about the seasonal mobility of

workers in the jurisdiction: Men worked in the Yodzotichii mills during the six months of dry season, and in

their parcels of land in house fields and in the boundaries during the six

months of water53. In the description of the archbishopric of Antequera (Oaxaca) we read the

following:

In the present year [1803], all the parishioners have not yet complied with the annual precepts of

confession and communion, because of the occupation in which they are engaged

in the sugar mills of the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of Tecomaxtlahuaca, which

is twelve leagues distant. Most people from this head town and subject villages

attend to them in grinding time, and this happens every year [...] (Huesca, Esparza & Castañeda, 1984: 334)54.

Locally, the need to provide sustenance to themselves once the system of

ecological complementarity was interrupted, and also by the previously

indicated monetisation of the tribute, explain the transfer of indigenous

labour from the gardens and fields to the mills, contrary to what the laws

indicated. But, what condition did the commoners who worked permanently in the cañada have? The comments we make below on the jurisdictional ascription shed light on

this question.

On the ecological level, new productive activities inevitably changed the

environment. As we have shown, at the end of the sixteenth century the

communities had already acquired very numerous herds of goats and sheep. They

used the slopes of the cañada to graze, or, from the middle of the seventeenth century, rent them to other

Spanish owners as flying ranches55. Although this type of livestock entails loss of forest mass and reduction of

soil productive capacity (Melville, 1994; Spores, 2007: 169, 405), the vegetal

denseness of the cañada minimized the negative impact observed in other areas of the Mixteca, as in the

Nochixtlán valley, where erosion is very evident. However, grazing always resulted in the

risk of damage to crops.

Although sugar cane was already present from the middle of the sixteenth

century, we believe that until its rise at the beginning of the eighteenth

century it continued to be combined with other crops associated with the milpa56, such as maize and chile, and crops of high economic value such as cocoa and

cotton, plus new ones, such as bananas57. When the sugar cane took over the bottom of the valley, the pine and oak

forests in the slopes and mountains, plus the ceibas and pochotes typical of the valley humidity, were demanded as fuel for the mill boilers and

to fabricate other production inputs58. The plantations also monopolized the water of the Chicahuaxtla river and its

tributaries, perhaps by similar means to those used to channel to the gardens

the severe flooding that inundated the alluvial plains during the rainy season.

Carlos Sempat (2006) postulates that the great demographic crisis that came

after the conquest –it is estimated a decrease in not less than 90%– severely affected certain forms of indigenous farming that required good social

organization. More lands also became available for Spanish enterprises. We

believe that the demographic decline and the territorial restructuring of the

towns and villages can be related to the abandonment of areas of cultivation on

terraces (coo yuu, in Mixtec language) in the small valley of Tlaxiaco, which demanded strict

organization of the labour and work (Pérez Rodríguez, 2016). In fact, sources show a population decrease of 65% in the Tlaxiaco

settlements in the cañada: in 1550 there were 197 tributaries, and as early as 1599 there were only 69.

By the end of the eighteenth century, total indigenous population in the

jurisdiction had significantly recovered: in 1550 there were 4,058 tributaries;

in 1599 they had been reduced to 2,039, and in 1777 they were 10,14659. However, Ángel Palerm (1972: 65) indicates that, allegedly, most of the irrigation systems

in Mesoamerican gardens had only local importance and did not require major

hydraulic works. This could have been the case of the cañada, which could explain the continuity of productive activities and the non-giving

ground to Spanish ambitions, and thereby, retention of lands in indigenous

hands. Another factor to examine is the possibility of seasonal mobilization of

workers. These two elements bring us to talk about jurisdictional relations.

The dependent villages on Tlaxiaco in the cañada of Yosotiche had two outstanding peculiarities with respect to the rest of the

jurisdiction: they reported to the authorities a smaller population number, and

administratively appeared to have a particular status. Regarding the second

point, in 1550 two localities existed under Teponaxtla, in turn subordinated to

Tlaxiaco. Fifty years later, this internal hierarchy had apparently diluted,

and three villages were mentioned in the “hot lands” with similar status: Santo Tomás Teponaxtla (today, San Juan Teponaxtla), San Juan (we do not know if it

corresponds to any current locality) and Santiago Yosotiche60. What attracts our attention is that, despite being villages under Tlaxiaco,

they did not have a government apparatus similar to the rest of them. The head

town was the only that had a governor, besides alcaldes (mayors), an alguacil mayor (in charge of justice), tequitlatos (in charge of tribute), regidores (councilors) and other positions, whereas the subject places exercised their

local power through alcaldes, alguaciles, mayordomos (kind of religious administrators) and tequitlatos. Despite in 1618 a royal cedula was issued establishing one alcalde and one regidor for 50 to 80 tributaries villages, two alcaldes and two, maximum four, regidores for those with more than 80 (Pastor, 1987: 88), it was not until 1703 when the

Viceroy granted permission to Santiago Yosotiche to annually appoint an alcalde, a regidor and an alguacil mayor (major sheriff)61. As a result and in a systematic way, in all the lawsuits previously alluded

hold by the control of the cañada, it was the “common and natives” of the head town of Tlaxiaco who came out in defense of the lands. This

situation continued until the mid-nineteenth century, when the disentailment

laws altered this type of communal property (Monaghan, 1990). We are facing a

territory nominally mentioned as subject villages, but without direct political

representation, the only one in the whole jurisdiction.

We believe that localities placed in the cañada could be settlements of terrazgueros ascribed to the cacicazgo and to the nobility of Tlaxiaco. The oral tradition characterizes these places

as foundations conducted by Tlaxiaco and Ocotepec to avoid introductions by

rival lordships. This was a very common strategy in Mesoamerica. Manuel Martínez Gracida (1883: “Yosotiche Santiago”) recalled that Santiago Yosotiche was formerly a subject place established here to guard the plots in “hot land”, and it was promoted later to the village category. For this reason it lacks

land, and the peasants have to rent those they need for their sowings62. Other places in the mountainous zone, San Pedro Yosotato and Santa Cruz

Nundaco, could also have been respectively set up by Tlaxiaco and Ocotepec to

avoid introductions (López Bárcenas in González & Sánchez, 2015: 148-49). Additionally, we know that this practice of founding

settlements with terrazgueros to expand the dominion of the lordship was carried out by the cacica of Tlaxiaco, Doña María de Saavedra: in 1581, she sent some families to “populate and guard” patrimonial distant lands near San Juan Teita; and, in 1590, established terrazgueros close to Malinaltepec (today, San Bartolomé Yucuañe) to found a neighbourhood called Ñuuyucu63.

In 1573, the powerful and wealthy cacique of Tlaxiaco, Felipe de Saavedra, inherited to his daughter María a great amount of lands that included gardens and milpas in the most productive regions, fruit trees and grazing and extracting natural

resources areas64. It was customary for the most valuable lands to be in hands of the nobility,

especially the cocoa gardens, because their use and circulation was linked to

the high social strata (Aranda, 2005: 1440). This matter supports the idea that

lands in the cañada were lordly patrimony. In 1587, María de Saavedra married Francisco de Guzmán, the powerful heir of the cacicazgo of Yanhuitlán65. Her properties were just so extensive that, in 1581, Doña María donated or sold some high-quality lands to the Dominican monastery of

Tlaxiaco. The cacica died in the middle of the decade of 1590 without descendants, so her direct

line of succession was extinguished. She had not made a will, and the town

council of Tlaxiaco claimed that just before her death she had stipulated that

her possessions should go to the community, which was finally authorized by the

Royal Audience66.

In spite of the fact that the cañada became property of the town council of Tlaxiaco, we believe that the domain

continued having an important lordly nature, as well as its inhabitants as terrazgueros, which favored their mobilisation as labour in the mills. The highly complex yuhuitayu model that we have detected allowed the existence of other chiefdoms subsumed

within the larger organization, and made the council an entity with lordly

power. In this sense, stands out the participation of the Chávez family, caciques of San Juan Ñumí and other neighbouring villages, all under Tlaxiaco, as council officers in

multiple occasions during sixteenth and seventeenth centuries67.

The awarding of land grants confirms Menegus’s (2009: 50, 56; 2015) idea that a significant proportion of the population

depended on lordly lands for their livelihood. Of the seventeen grants for

cattle ranches and other necessities given during the sixteenth century, four

were addressed to caciques, five to noble chiefs, one to the encomendero, and the largest number, six, to the community, but as propios lands68.

Finally, it is possible that the survival of these “disguised” seigniorial relationships could have favoured the retention of lands in

indigenous hands and prevented the advance of Spanish property, together with

the initial little interest shown by the Spaniards in the exploitation of the

land in the Mixteca, expressing a greater tendency to control commercial

activity (Romero, 1994). A group of four royal orders issued in 1591 provided

the legal device to allow the Crown to appropriate the barren lands, considered

realengas (of the royal domain), and to grant them in exchange for a payment. An

ambitious project of congregation of villages, strongly promoted by the Viceroy

Conde de Monterrey, followed these actions (Sempat, 2006). The intention of

this plan, besides ensuring an optimal tax and religious control, was to

evacuate indigenous lands to be placed in operation by Spaniards. The judge who

visited the jurisdiction of Tlaxiaco in 1599 wanted to move the villages of the

cañada to the Triqui region of Copala, about 20 km northwest69. It is estimated that the effects in New Spain of the 1591 royal orders were

lower to those expected by the Crown, as well as failed the immense majority of

the congregational plans in the Mixteca, also, the one of Tlaxiaco (Martín Gabaldón, 2015)70. This ensured a “massaged” continuity of indigenous property, adequate to the Hispanic regulation.

5. Conclusions

The Conquest and the construction of the colonial world unavoidably altered the

indigenous organization in all its spheres. At the biological level, the

introduction of some vegetable species with views to an intensive and

commercial exploitation severely modified ecosystems and displaced traditional

forms of production that guaranteed the subsistence and economic order of

lordships. In the case study shown here, sugarcane significantly altered the

ecological complementarity around the maize exchange practiced in the Yosotiche

ecosystem, but, paradoxically and considering the community and lordly levels,

this fact did not necessarily act to the detriment of these Indian villages,

unlike what happened in other parts of New Spain.

Taking advantage of the legal artifices provided by the colonial administration,

and thanks to the relatively little interest in the region by Spaniards until

the eighteenth century, both communities and caciques managed to retain their lands, although the implementation of a European model

of territoriality and jurisdiction provoked continuous litigations for the

possession of such productive fields. What we observed in this region matches

with the features detected by Arrioja and Sánchez Silva (2012: 24-5)71 among the colonial Oaxacan towns:

The existence of communal lands legally ascribed to the indigenous governments

and benefited by the so-called common Indians; the permanence of lands related

to lordships and laboured by terrazgueros or macehuales; [and] the simulation of an agrarian market where the Indian governments leased the

access and usufruct of their common lands in favour of neighbouring towns,

haciendas, ranches, caciques and Indians with some economic solvency.

However, contrary to the statement also made by these authors, that says that

agricultural units of European origin constantly suffered the lack of

indigenous labour force (Arrioja & Sánchez Silva, 2012), we know that the sugar mills involved plentiful Mixtec

workforce in Yosotiche in particular, and in general, in the ancient

jurisdictions of Tlaxiaco, Ocotepec, Chicahuaxtla and Putla. The observed

situation also differs from that identified in the haciendas of the Valley of Oaxaca by Taylor (1998: 153), where the fulltime labour came

from debt peonage.

This situation can be explained by analysing the composition of the yuhuitayu and their conversion into “head-subjects complexes”. In particular, Tlaxiaco soon revealed a strong community (represented by the

council) that managed and benefited from the livestock and agriculture

practised in multiple lands of its patrimony, which also allowed the town to

set itself up as an important regional trade centre. But the town council and

the governing structure of its manifold subject villages masked lordly

relations rooted in the pre-Hispanic tradition possibly related to its former

condition of “compound lordship”72. These relationships allowed to exercise power over their commoners as terrazgueros and thus mobilise the necessary workforce to attend to the cultivation and

processing of cane in the mills established from the sixteenth century, which

gained momentum in the eighteenth century in Spanish hands on lands rented to

the Indians.

AKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to express my special thanks to the Centre for Latin American

Research and Documentation (CEDLA, Amsterdam) for partially funding this

research. I am also immensely grateful with John Monaghan (University of

Illinois at Chicago) for showing me his notes on the documents kept in the

today ruined municipal archive of Yucuhiti, and to Manuel Hermann for accompany me on my field trip in the cañada of Yosotiche. Also, thanks to Maira Córdova Aguilar and Huemac Escalona Lüttig for sharing their knowledge on some specific aspects addressed in this

work. Finally, I am grateful to the 3 anonymous reviewers for their critics and

suggestions on the first version of text.

REFERENCES

Aranda, L. (2005). El uso del cacao como moneda en la época prehispánica y su pervivencia en la época colonial. In C. Alfaro, C. Marcos & P. Otero (Coords.), XIII Congreso Internacional de Numismática, Madrid, 2003 (pp. 1439-50). Madrid: Ministerio de Cultura.

Arrioja, L. A. & C. Sánchez Silva (2012). Pueblos, reformas y contrariedades agrarias: Oaxaca, 1742-1857. In L. A. Arrioja & C. Sánchez Silva (Eds.), Conflictos por la tierra en Oaxaca: De las reformas borbónicas a la reforma agraria (pp. 21-42). Zamora/Oaxaca de Juárez: El Colegio de Michoacán/Universidad Autónoma Benito Juárez de Oaxaca.

Berdan, F. & Rieff, P. (1997). The Essential Codex Mendoza. Berkeley/Los Angeles/London: University of California Press.

Chance, J. K. (2004). La casa noble mixteca: Una hipótesis sobre el cacicazgo prehispánico y colonial. In N. M. Robles (Ed.), Estructuras políticas en el Oaxaca antiguo: Memoria de la Tercera Mesa Redonda de Monte Albán (pp. 1-25). México, DF: CONACULTA/Fondo Editorial Tierra Adentro.

Chance, J. K. (2010). From Lord to Landowner: The Predicament of the Late Colonial Mixtec

Cacique. Ethnohistory, 57 (3), 445-66.

Chassen, F. R. (2003). Santa María Yucuiti, la lucha tenaz de un pueblo. Cuadernos del Sur, 9 (18), 5-16.

Cronon, W. (1983). Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England. New York: Hill & Wang.

Crosby, A. W. (1972). The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492. Westport: Greenwood.

Dahlgren, B. (1990 [1954]). La Mixteca: Su cultura e historia prehispánicas. México, DF: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Doesburg, S. van (2003). El siglo xvi en los lienzos de Coixtlahuaca. Journal de la Société des Américanistes, 89 (2), 67-96.

Esparza, M. (Ed.) (1994). Relaciones Geográficas de Oaxaca, 1777-1778. México, DF: Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social.

Gallini, S. (2005). Invitación a la historia ambiental. Tareas, (120), 5-28.

García Castro, R. (Ed.) (2013) Suma de visitas de pueblos de la Nueva España, 1548-1550. Toluca: Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México.

González, I. & Sánchez R. (2015). El señorío de Ocotepec. In M. Hermann (Coord.), Configuraciones territoriales en la Mixteca. I: Estudios de Historia y

Antropología (pp. 129-73). México, DF: Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social.

Hamnett, B. (2002). Los pueblos indios y la defensa de la comunidad en el México independiente, 1824-1884: El caso de Oaxaca. In A. Escobar, R. Falcón & R. Buve (Eds.), Pueblos, comunidades y municipios frente a los proyectos modernizadores en América Latina, siglo xix (pp. 189-205). San Luis Potosí/Amsterdam: Colegio de San Luis/Centre for Latin American Research and

Documentation.

Hermann, M. (2005). Códices y señoríos: Un análisis sobre los símbolos de poder en la Mixteca prehispánica. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. México, DF: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Hermann, M. (Coord.) (2015). Configuraciones territoriales en la Mixteca. I: Estudios de Historia y

Antropología. México, DF: Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social.

Hoekstra, R. (1990). A Different Way of Thinking: Contrasting Spanish and Indian Social and

Economic Views in Central Mexico (1550-1600). In A. Ouweneel & S. Miller (Eds.), The Indian Community of Colonial Mexico: Fifteen Essays on Land Tenure,

Corporate Organizations, Ideology and Village Politics (pp. 60-86). Amsterdam: Centre for Latin American Research and Documentation.

Huesca, I., Esparza, M. & Castañeda, L. (1984). Cuestionario del Sr. don Antonio Bergoza y Jordán, obispo de Antequera, a los señores curas de la diócesis. Vol. i. Oaxaca de Juárez: Gobierno del Estado de Oaxaca.

Jansen, M. (2004). La Dinastía de Ndisi Nuu (Tlaxiaco): El Códice Bodley Reverso. Latin American Indian Literatures Journal, 20 (2), 146-88.

Kowalewski, S., Balkansky, A. K., Stiver, L. R., Pluckhahn, T. J., Chamblee, J.

F., Pérez Rodríguez, V. & Smith, C. A. (2009). Origins of the Ñuu: Archaeology in the Mixteca Alta, Mexico. Boulder: University Press of Colorado.

Lockhart, J. (1992). The Nahuas after the Conquest: A social and Cultural History of the Indians of

Central Mexico, Sixteenth through Eighteenth Centuries. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Martín Gabaldón, M. (2015). Balance general de los traslados de pueblos y congregaciones en la

Mixteca, siglos xvi y comienzos del siglo xvii. In M. Hermann (Coord.), Configuraciones territoriales en la Mixteca. I: Estudios de Historia y

Antropología (pp. 175-202). México, DF: Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social.

Martínez Gracida, M. (1883). Colección de “cuadros sinópticos” de los pueblos, haciendas y ranchos del Estado Libre y Soberano de Oaxaca. Oaxaca de Juárez: Imprenta del Estado.

McNeill, J. R. (2005). Naturaleza y cultura de la historia ambiental. Nómadas, (22), 12-25.

Melville, E. G. K. (1994). A Plague of Sheep: Environmental Consequences of the Conquest of Mexico. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Menegus, M. (2005). El cacicazgo en la Nueva España. In M. Menegus & R. Aguirre (Coords.), El cacicazgo en Nueva España y Filpinas (pp. 13-70). México, DF: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México/Plaza y Valdés.

Menegus, M. (2009). La Mixteca Baja: Entre la Revolución y la Reforma: Cacicazgo, Territorialidad y Gobierno, siglos xviii-xix. Oaxaca de Juárez: Universidad Autónoma Benito Juárez de Oaxaca/Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana/Congreso del Estado de Oaxaca.

Menegus, M. (2015). Cacicazgos y repúblicas de indios en el siglo xvi: La transformación de la propiedad en la Mixteca. In M. Hermann (Coord.), Configuraciones territoriales en la Mixteca. 1: Estudios de historia y

antropología (pp. 205-20). México, DF: Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social.

Monaghan, J. (1990). La desamortización de la propiedad comunal en la mixteca: Resistencia popular y raíces de la conciencia Nacional. In M. A. Romero (Comp.), Lecturas históricas del estado de Oaxaca. Vol. iii (pp. 343-85). México, DF: Gobierno del Estado de Oaxaca/Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

Monaghan, J. (1994). Irrigation and Ecological Complementarity in Mixtec Cacicazgos. In J. Marcus & J. F. Zeitlin (Eds.), Caciques and their People: A Volume in Honor of Ronald Spores (pp. 143-61). Ann Arbor: Museum of Anthropology.

Motta, A. & Velasco, A. M. L. (2003). La Cañada Oaxaca/Puebla, una región azucarera del siglo xvii al pie de la Sierra Madre Oriental. Antropología. Boletín Oficial del Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, (69), 18-26.

Ouweneel, A. & Miller, S. (Eds.) (1990). The Indian Community of Colonial Mexico: Fifteen Essays on Land Tenure,

Corporate Organizations, Ideology and Village Politics. Amsterdam: Centre for Latin American Research and Documentation.

Palerm, A. (1972). Distribución geográfica de los regadíos en el área central de Mesoamérica. In A. Palerm & E. Wolf (Eds.), Agricultura y civilización en Mesoamérica (pp. 30-61). México, DF: Secretaría de Educación Pública.

Pastor, R. (1987). Campesinos y reformas: La Mixteca 1700-1856. México, DF: Colegio de México.

Pérez Rodríguez, V. (2016). Terrace Agriculture in the Mixteca Alta Region, Oaxaca, Mexico:

Ethnographic and Archeological Insights on Terrace Construction and Labor

Organization. Culture, Agriculture, Food and Environment, 38 (1), 18-27.

Reyes, Fray A. de los (1890 [1593]). Arte en legua mixteca. Alençon: Typhographie B. Renaut de Broise.

Romero, M. A. (1990). Economía y vida de los españoles en la Mixteca Alta: 1519-1720. México, DF: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

Ruiz Medrano, E. (1991). Gobierno y sociedad en Nueva España: Segunda Audiencia y Antonio de Mendoza. Zamora: Gobierno del Estado de Michoacán.

Sánchez Silva, C. (1998). Indios, comerciantes y burocracia en la Oaxaca poscolonial, 1786-1860. Oaxaca de Juárez: Instituto Oaxaqueño de las Culturas/Fondo Estatal para la Cultura y las Artes/Universidad Autónoma Benito Juárez de Oaxaca.

Sandoval, F. B. (1951). La Industria del azúcar en la Nueva España. México, DF: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Schwartz, S. B. (Ed.) (2004). Tropical Babylons: Sugar and the Making of the Atlantic World, 1450-1680. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Sempat, C. (2006). Agriculture and Land Tenure. In V. Bulmer-Thomas et al. (Eds.), The Cambridge Economic History of Latin America. I: The Colonial Era and the

Short Nineteenth Century (pp. 275-314). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Smith, M. E. (1973). Picture Writing from Ancient Southern Mexico: Mixtec Place Signs and Maps. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Spores, R. (1967). The Mixtecs Kings and their People. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Spores, R. (1974). Marital Alliance in the Political Integration of Mixtec Kingdoms. American Anthropologist, 76 (2), 297-311.

Spores, R. (2005). El impacto de la política de congregaciones en los asentamientos coloniales de la Mixteca Alta,

Oaxaca: El caso de Tlaxiaco y su región. Cuadernos del Sur, (22), 7-16.

Spores, R. (2007). Ñuu Ñudzahui, la Mixteca de Oaxaca: La evolución de la cultura mixteca desde los primeros pueblos preclásicos hasta la Independencia. Oaxaca: Intituto de Educación Pública del Estado de Oaxaca.

Taylor, W. B. (1998). Terratenientes y campesinos en la Oaxaca colonial. Oaxaca de Juárez: Instituto Oaxaqueño de las Culturas/Fondo Estatal para la Cultura y las Artes.

Terraciano, K. (2001). The Mixtecs of Oaxaca: Ñudzahui History Sixteenth through Eighteenth Centuries. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Wobeser, G. von (2004). La hacienda azucarera en la época colonial. México, DF: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Worster, D. (Ed.) (1989). The Ends of the Earth: Perspectives on Modern Environmental History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zavala, S. A. (1973 [1935]). La encomienda indiana. México, DF: Porrúa.

NOTAS A PIE DE PÁGINA / FOOTNOTES

10. This modern streamlining was based on the geographic and cultural criteria

previously observed by the ancient Mixtecs, before the arrival of the

Spaniards: the Mixteca Alta Was known as ñudzavuiñuhu, “land of the people of the rain”; the Mixteca Baja as ñuniñe or ñuiñe, “hot land”; and Mixteca de la Costa as ñundaa, “plain land”, or nundehui, “land of the sky” (term associated with sahandevui, “foot of the sky”, referencing the horizon) (Reyes, 1890: I-II). In Figure 1 we have incorporated

the region called Montaña de Guerrero, because coexist Mixtec villages with Nahuas and Me’phaa or Tlapanec people.

12. For a discussion regarding the importance of kinship, see Pastor (1987: 28-36), Terraciano (2001: chap. IV) and Chance (2004).

16. “Diligencias para la congregación de Tlaxiaco efectuadas por Ruy Díaz Cerón, 1599” (Taller de Restauración del Exconvento de Santo Domingo, Oaxaca de Juárez). Ronald Spores (2005) published a brief summary and some comments on it.

19. “Sobre la congregación de Tlaxiaco”, 1552 (Newberry Library, Ayer MS 1121, fs. 195v-196r); “Mandamiento para la congregación de Tlaxiaco”, 1553 (Library of Congress, Kraus MS 140, f. 415).

20. “Suma de visitas de pueblos de la Nueva España” (1548-1550), following the transcription by García Castro (2013: 386-388).

22. “Diligencias para la congregación de Tlaxiaco efectuadas por Ruy Díaz Cerón, 1599”.

25. In the documents dated 1588 and 1591 preserved in the Archivo Municipal de

Yucuhiti are recorded the people who were benefiting gardens and plots in the

disputed lands between Tlaxiaco and Ocotepec. They mention the names of the

farmers and lands, in Mixtec language, the number of plots cultivated, its

products (cocoa, banana, maize, chilli and cane) and the extension, expressed

in number of fathoms.

41. AGEPEO, Alcaldías Mayores, leg. 56, exp. 17.

53. “Relación geográfica de 1777. Tlaxiaco” (Esparza, 1994: 383). Translation by the author.

55. See note 40.

60. “Diligencias para la congregación de Tlaxiaco efectuadas por Ruy Díaz Cerón”, 1599.

66. The documents that prove these data were consulted by Ronald Spores (2007: 310-11) in the former Archivo Municipal de Tlaxiaco and in the also

former Archivo Histórico Judicial de Oaxaca. Unfortunately, the two documents referred to by him are

not currently available.

69. “Diligencias para la congregación de Tlaxiaco efectuadas por Ruy Díaz Cerón”, 1599 (Taller de Restauración del Exconvento de Santo Domingo, Oaxaca de Juárez).